Amore: Learning When to Listen Before I Sing

Some music needs very few words. It just wants to be heard.

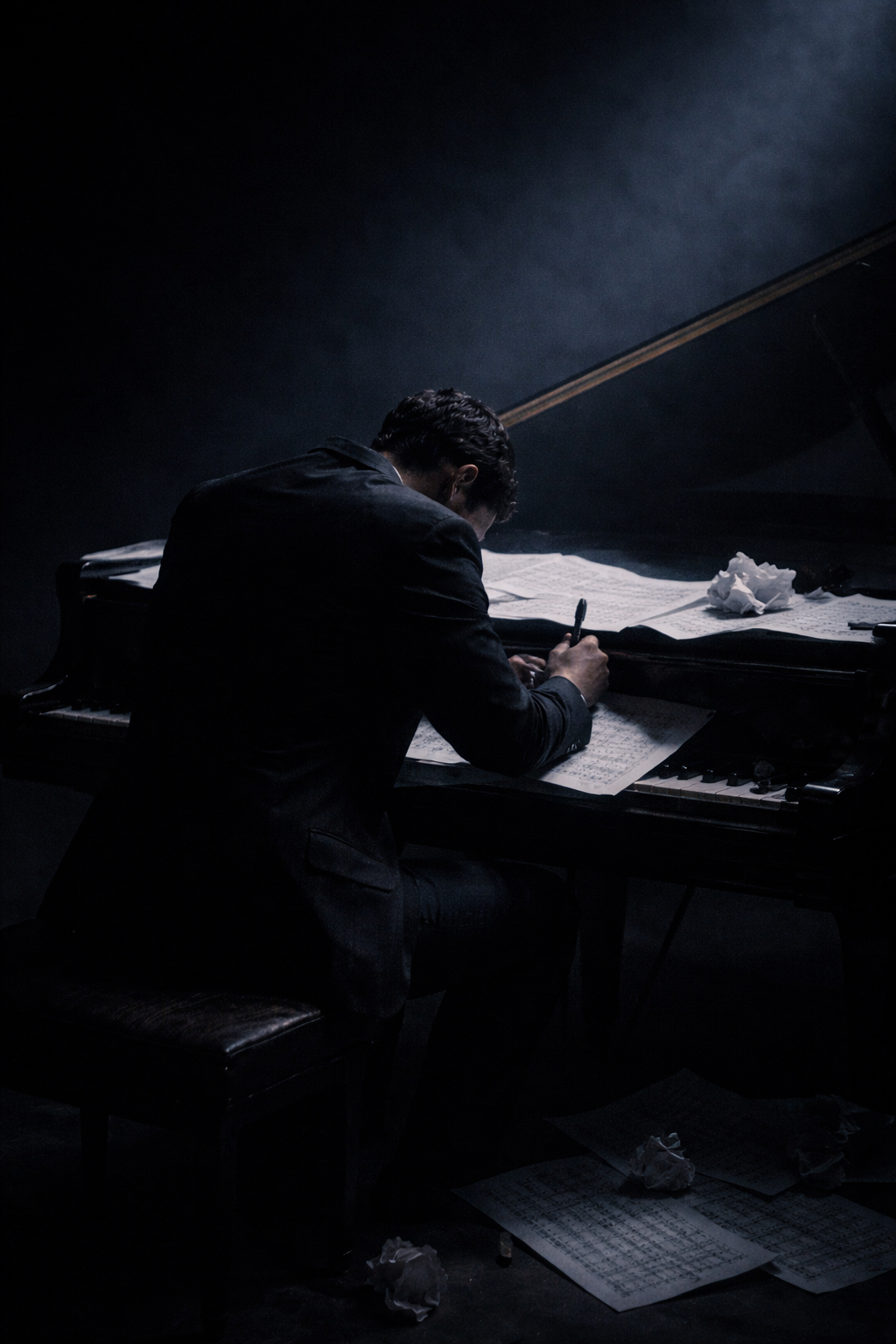

Amore began the way many honest pieces of music do—not with a plan, not with a release strategy, not even really with an audience in mind—but as an act of survival, an act of release.

It started as a piano sketch written in the aftermath of a relationship ending—and not my own. There was no structure imposed on it. There was no concern for whether it would ever become anything more than a momentary release. It was fast, reckless, insistent, and restless. A minor key that never relented. A tempo that almost felt impatient, as though the hands playing it needed to outrun something before it could catch up.

When I first heard it, I understood immediately what it was: a post-breakup therapy session. Not the quiet kind. Not reflective or gentle. It was the kind of emotional purging that happens when grief and anger occupy the same body at the same time. And yet, there was so much beauty. So much beauty. It was fractured, hurried, unresolved—never pausing to take a breath. Most importantly, it didn’t wait for permission.

As with many singers—especially us sopranos—I did what we are trained to do. I tried to sing over the piano, turning it into a backdrop, an accompaniment to my own melody.

The earliest versions of Amore were in French. I took the piano and wrapped it in mid-range vocals, layered text, fuller phrasing. It softened the piece. It gave it an impressionistic sweetness, almost like rain pattering on water—pretty, restrained, palatable, and boring.

At the time, I didn’t realize that I was competing with the music rather than complementing it. And with this particular composer, that is the one thing you can never do. There is a main character in his work, and it simply isn’t the voice.

It’s the piano.

His music does not make space for a vocalist in the traditional sense. It doesn’t step back and wait for the voice to lead. The piano is the melody. It is the narrative engine. It already has a story to tell, and it tells it clearly—insistently, sometimes mercilessly. If you attempt to dominate it, you lose the entire point of the piece. And so does the audience.

That realization didn’t come immediately. It came slowly, and honestly, a little painfully.

As a soprano, we are trained to be the focal point—the line, the authority, the voice that everything else supports and accompanies. But original music does not owe you that hierarchy. There is no inherited structure. There is no roadmap. You have to understand the architecture and see it in your mind’s eye before it can be built, which requires respect for what already exists before you enter the picture.

This was the third piece I had created with this composer, and by this point, a pattern had already emerged. Every time I began a new project with him, I had to be reminded—sometimes through painful trial and error—that my role was not to lead. It was to follow. To find the rhythm and flow of what was already happening.

I had to stop singing and just sit and listen.

So I went back to the piano. I listened without singing, without planning where my voice would enter. I stopped trying to fix the broken perfection of what was already there. And that’s when she spoke to me. That’s when the real story revealed itself.

There was far more heartbreak and anger inside of it than I had been willing to hear at first. It wasn’t asking to be accompanied. It needed time. It needed space.

And that’s when I heard her voice—the one she tried to say softly in the first verse, but was drowned out by the piano. I heard what she really wanted to say to him.

Sei il mio amore.

So I allowed the first verse to belong entirely to the piano, as it always wanted to.

With precaution and a gentle introduction, only after the piano had fully spoken and said his piece—after letting him escape his own memories—I obediently sang the words I felt her singing in the background and brought the second voice to life.

She enters late, in verse two. And when she does, she doesn’t interrupt the piano’s emotional trajectory. I realized then that she exists alongside it—quietly defensive. Quiet, but defensive.

The sadness in her voice is different from the anger in the piano. She knows what she does not yet want to admit to herself: that this is ending, and that love will not repair it. Still, she tries.

As the voice climbs higher, something subtle but devastating happens. The piano refuses to soften in response. It intensifies. It plays more aggressively, almost as if trying to outrun her words.

She tries anyway, repeating over and over again, sei il mio amore.

And nearing the end of the piece, language itself begins to collapse. The phrase you are my love disappears entirely and gives way to the piano line alone. Only the melody remains—where she can no longer continue.

She repeats, amore, amore, as if meaning has become too much for words to carry, and can only be expressed through the languishing strings of the violin.

As another instrument enters and echoes the vocal line in a fragile call and response, it feels less like harmony and more like a last-ditch effort—what lingers after the voice can no longer sustain itself.

And the piano, having outlived the rest—having outlived everything—continues on alone.

There is no resolution. No cadence that tells you everything will be okay. And just as abruptly as the piano began, it ends, as many relationships do: mid-thought, mid-emotion, and without the grace of closure.

What I love about creating original music is exactly this: there is no precedent. There is no interpretation to follow. It is complete creative freedom—discovering the rules through trial and error, and often learning them by breaking them first.

As a co-composer and co-writer, my responsibility was not to impose myself on this piece, but to respect the story that was already being told.

It’s like double dutch. You cannot change the rhythm of the ropes. You have to watch. You have to observe. You have to feel the timing before you jump in. If you don’t enter at exactly the right moment, you disrupt the pattern already in motion.

At first, I was beating against the rhythm of the song—competing, trying to assert myself in the narrative when all along, the narrative already existed.

When I finally stopped and listened, the music revealed itself to me.

Amore is the result of that listening.

It is not a love song in the traditional sense, but a record of two emotional truths existing simultaneously—and never quite meeting. To tell this story from a third-person perspective while singing from the first person was an incredibly visceral experience.

As with all original music, it taught me the importance of listening before I sing—of finding what already exists, which can take years, along with focus, humility, and patience. Like any meditative practice, this is what a good musician does when engaging with music that was already in motion before adding their own voice to it.

I hope I have done this music justice—for the story it told and for the people involved. Because at the end of the day, there were real human lives inside this piece. Though they shall remain unnamed, I hope I honored them while still finding my own way—weaving a narrative that is wholly my interpretation.

As we approach Valentine’s Day, a time that holds many meanings for many people, it felt appropriate to release this song now. Love can be beautiful, happy, and warm—but we are all moving through different phases of relationships at the same time.

This is one of the most overlooked phases of the year.

And it deserves a place in the story, too.

Listen to Amore here, and fall in love like I did… all those years ago.

https://youtu.be/PRBJfUv5ENk?si=i2vB4P2UKS02QxcZ